Doom (1993) | DOOM.WAD

id Software

This review was originally posted in parts to Medium and tumblr.

On December 10, 1993, a group of guys who liked heavy metal and cats uploaded a game they made to the file server at University of Wisconsin–Madison. Within seconds, the university’s entire network crashed under the strain of trying to accommodate ten thousand people all trying to download the game at once. Doom had come to the world, and video games were never the same again.

In the annals of early to mid 90s PC gaming, id Software was king. Their early stuff — like the cute platformer Commander Keen or the early first person shooter Wolfenstein 3D — made them famous. But Doom would make them rich. Fast-paced and hyper-violent, Doom was an addictive, heady mix of heavy metal, science fiction horror and copious gore. It outraged moral guardians and enthralled even people who didn’t really play games. It was among the number of games effectively put on trial during the 1994 United States Senate hearings that would eventually result in the founding of the Entertainment Software Ratings Board, a collection of the most deadpan people on Earth whose job it is to look at video game footage and tell you if it’s appropriate for children or not.

There’s been a lot of ink spilled over this game over the last 30 years, and no doubt we’ll see more in the mainstream gaming press. But for me, I can only really talk about my experience with it. My first time playing Doom was at a neighbor’s house. Mr. Closson was usually gone during the day but his wife would let me sneak over and play games on his computer in the basement. He had stuff like SimCity, Iron Helix, and eventually Wolfenstein 3D. This latter one he told me was not for kids, but he didn’t really protest when I played it. Nor did he do much more than shrug his shoulders when I came over one day and he had the shareware episode of Doom. I was immediately enthralled, but the (at the time) extreme violence and the demonic enemies meant I could never, ever let my religious fundamentalist mom see this. (We’re talking about a person who wouldn’t let me rent Marble Madness for the NES because she misheard the title as Marble Magic and decided it was devil worship.)

After acquiring a copy for myself, I played Doom’s shareware episode on my own computer off and on over the next few years, mixed in with Doom 64, Duke Nukem 3D (and its Nintendo 64 port), Half-Life, and the full version of Quake, which was a gift from a friend of my mom’s and to this day I’m confused as to why he did that, as it seemed to be a gift to my mother who subsequently passed it on to me. Not having heard of software piracy, my only experience with the second episode of Doom for most of the 1990s was the Super Nintendo port of the game; I never actually owned a legal copy of the PC version until I bought it off Steam about a decade ago. I did, however, own Doom II, my mom randomly — and inattentively — picking it up for me for $15 around the turn of the millennium when I found a budget release of the game at a department store. And while I played the shit out of that, of course, plus the zillion user-made addons that required it, Doom 1 remained tantalizingly out of reach for a little while longer.

I’ve played a lot of shooters over the years. While I find myself always eventually returning to Duke Nukem 3D, it was Doom that captured my heart first, and it’s Doom — and its extraordinary legacy — that most defines everything that came after it. From humble beginnings with a nascent fandom that lived on Usenet to the source port GZDoom taking its place as a viable option for commercial games like Selaco, Doom has always been a reflection of — and an influence on — the broader first person shooter universe. Doom deathmatch was a violent form of laser tag you could play at home, laying the groundwork for the likes of Quake. Early megawads reflected the influence of Quake and Quake II (especially apparent in the Gothic Deathmatch series and The Darkening 2, respectively.) Doom 3, the unfairly maligned middle child, showed the influence of Half-Life and System Shock 2. And the Doom 2016/Eternal reboot has been a love letter to not just its predecessors, but to the entire genre and id Software’s history.In a way, Doom has become a sort of rite of passage for computer engineering over the years. We’ve all seen the memes about running Doom on everything from calculators to pregnancy tests. It’s seen a billion ports, official and otherwise; back in the wild and woolly days of console ports, Doom was ported to almost every contemporary console under the sun. The Super Nintendo version is a technical marvel even if the port itself isn’t very good; the Sega 32X version by comparison has no redeeming qualities. The Panasonic 3DO version — widely regarded as the worst port — is mostly interesting as a historical curiosity, developed in ten weeks almost entirely by industry legend Rebecca Heineman, who had to scramble to get it done because Randy Scott, CEO for Art Data Interactive and all-around piece of shit, made a lot of promises that simply couldn’t be kept. Not having the time to rewrite the music engine, Heineman simply hired Scott’s church band to play some covers of the music and wrote a simple engine that played back the audio stream from the disc, and most people agree that the live-band covers are the one thing the port has going for it. The Atari Jaguar version, meanwhile, is probably the most important console release of the 90s. While like most every other console port, it is markedly inferior to the original, even outright lacking music entirely, it was mostly developed by id Software’s coding wizard, John Carmack himself; it also serves as the basis for most of the following console ports, which is why so many of them use the Jaguar version’s simplified level geometry even on platforms that could theoretically handle more detail, such as the PlayStation version, which otherwise made up for it with colored lighting, re-done sound effects and a dark ambient score for a drastically different, scarier atmosphere.

(The Jaguar version also had the best commercial.)

Doom doesn’t really have much of a storyline, nor does it need one. What’s there is rudimentary and mostly told in the manual, a remnant of the expansive universe erstwhile id Software founder Tom Hall tried to build before most of his ideas were scrapped in favor of a lean-n’-mean arcade shooter. Doom is a story of the future, and it goes a little something like this: you’re a Marine, a real tough hombre, reassigned to Mars as punishment for assaulting a superior officer who ordered you to fire on civilians. Your posting on Mars is run by the Union Aerospace Corporation, a military contractor currently involved in teleportation experiments. One day the shit hits the fan and the distress signal from UAC’s base on the moon of Phobos is pretty concerning, while Deimos just vanishes right out of the sky. You and your team are dispatched to Phobos to investigate, with you establishing a perimeter while the others head inside. What you hear on the comms isn’t good, and when all goes silent, you realize it’s up to you, so you cock your pistol and head on in. The rest of the story is told at the end of each of the three episodes the game presents, the episodic structure an artifact of the shareware days of PC gaming, something that wouldn’t really go away until around 1997 or 1998 when the PC became a popular enough gaming platform to have its own space in the retail market.

Doom is scary. While most of the shareware episode, charmingly titled “Knee Deep in the Dead,” is straightforward, with its cloudy sky casting rheumy daylight on a gloomy complex of concrete and steel, I remember as a child being scared out of my mind on the last level, with the two bruisers waiting for me at the top of the elevator. I did eventually conquer my fear, and subsequently the bosses, but I was taken aback by the nihilistic ending, of stepping on a sinister pentagram and being teleported into a dark room where you’re immediately torn apart by monsters. The second episode, titled “The Shores of Hell,” ups the ante a bit by having you explore a laboratory complex, previously mysteriously disappeared into thin air, and which seems to be slowly converting into something more familiar to the hellish denizens who now occupy it: brick and stone and flame, with more dark rooms and twisty mazes being lurked in by the game’s mid-tier heavy hitters, including the bruisers’ relatives. The third episode, “Inferno,” takes things to their logical conclusion as you take the fight to Hell itself, stepping through fields of innards and wading through seas of blood as hordes of monsters hunt you down. The Cyberdemon, the hulking, lethal monstrosity that occupies the boss level of the second episode, makes a return in a select spot here for the express purpose of scaring you shitless. And over all of this is a MIDI soundtrack that bounces between the thump and grind of heavy metal and moody ambient pieces, each track striking its own tone for the level. The iconic theme for Doom’s first level is a sort of Metallica salad, bits and pieces of random riffs thrown together for a level that is short and quick — only for the next level to be a much larger outing, with the music slowing down appropriately. This frequent tonal contrast is a defining element of the game for me, the kind of thing that drew me to Duke Nukem 3D with its cartoon protagonist and parody porno vibe slathered in a moody, apocalyptic aesthetic, and it’s something that I dearly miss in the newer Doom games.

Compared to the later games in the Classic Doom canon (that is, Doom II, Final Doom and Doom 64,) Doom ’93 is a more sedate, slow-paced game. The followup would introduce an expanded bestiary, but Doom 1 is relatively lacking in mid-tier enemies. There’s plenty of gun-toting zombies and fireball-tossing leathery brown imps to soak up your ammunition; less common are the big pink musclebound bastards, melee-focused and who for some reason get the capital-D Demon moniker (as if the rest of the cast aren’t demonic themselves) but are more affectionately called pinkies, often appearing in groups to overwhelm the player, taking twice again as much punishment over the lower-tier trash, but finding the chainsaw will make short work of them and their half-invisible spectre brethren. These make up the entirety of the forces you fight in the first episode, the rest are shareware-gated. Episode two introduces us to the lost soul, a flying, flaming skull with a simple charge attack; more dangerous is the iconic cacodemon, a cyclopean floating ball of gas and red flesh that belches ball lightning at you. The upper end of the mid-tier is the monstrous satyr known as the Baron of Hell, first appearing as a twin pair of bosses at the end of the first episode only to return as a recurring threat in later episodes. The Barons are by far the greatest threat you’ll face for most of the game, as while they’re slow, they hit hard, and they go down even harder. It takes between five and six rockets to the face to put them down, which is more than double what’s needed for the rest, even the caco. At the upper tier are the two biggest bastards: the Cyberdemon and the Spiderdemon Mastermind. The former is a twenty-foot-tall hulking cyborg minotaur that can splatter you with just one rocket to the face; the latter is an angry alien brain of sorts piloting a four-legged mobile weapon platform that can turn you into Swiss cheese in an instant. What’s interesting to me is the biomechanical theme of these two enemies compared to the more naturalistic bent of the rest of the cast; it has implications for what Hell’s ultimate goals are, and is also an early indicator of a recurring theme of bloody cybernetics that id Software would return to repeatedly over the coming decades.

With such an array of terrifying enemies, your arsenal feels curiously low-key, even antique, in comparison. You start out with just your pistol and some brass knuckles; punching your enemies is a dicey proposition on all but the weakest fodder unless you get your hands on a chainsaw, which is useful on monsters that flinch easily, or a berserk pack, which dramatically boosts your melee damage. The pistol is a classic example of a great weapon to get a better one with, though it does have some very limited usefulness at extreme distances thanks to its high accuracy. The shotgun will be your workhorse for much of the game, pumping out a steady beat of high damage with plentiful ammo to keep it fed. The chaingun — basically a rotary cannon and a holdover from Wolfenstein 3D — is an improvement over the pistol, achieving accuracy through superior firepower, but it’s mostly useful as a backup to the shotgun. The rocket launcher will be perpetually underfed but it makes for a fantastic room clearer as well as helping delete those pesky barons, just mind you don’t blow yourself up in the process. The final two weapons, the first of which you only get in episode two and the latter being only available in the third episode, are reminders that this is, technically, a science fiction setting, with the plasma rifle spewing out a firehose of plasma balls to melt your enemies with, and the BFG 9000 (don’t ask what the acronym means) launching a single massive plasma ball that, through some complicated and slightly unreliable trickery, will do terrific damage to every enemy in sight.

In addition to the arsenal you’ll encounter a small array of powerups; the aforementioned berserk pack lasts until you exit the level despite a common misconception that the effect fades along with the red filter it places over your vision. Also laying around are light amplification goggles, which turn everything fullbright (some ports like GZDoom restore the green night-vision tint that was originally intended during development;) backpacks that permanently double your ammo limit (at least the first one you pick up, the rest just give you ammo;) radiation suits that last a short time and allow you to walk on most damaging surfaces; and a device that fills out your automap for the level. There are also more supernatural tools at your disposal, giving you temporary powers like invulnerability (which also turns everything inverse monochrome,) partial invisibility (basically rendering your weapon sprite that same fuzzy blob as spectres while making enemies randomly shoot to one side of you or another, which can actually be dangerous if you’re used to constantly bobbing and weaving;) and the supercharge, a strange glowing blue sphere with a ghostly face that gives you an instant 100% health on top of what you already have, up to a maximum of 200%. You’ll also find armor in green and blue flavors, offering up to 100% and 200% armor respectively, though the actual damage reduced is increased on the blue armor, which means that it’s sometimes more strategic, if your blue armor percentage is low, to leave green armor until your blue armor is further depleted. There’s also the mysterious health and armor bonus items, which each boost your percentages by 1, even over the soft cap of 100%, but the provenance of which is unclear.

Being a (pseudo) 3D game made in the early 90s, with a dedicated arcade focus, Doom’s level design is that same abstraction that pervades most shooters of the era. You won’t find much in the way of anything that looks like a realistic habitable space; regardless of which of the three designers were at the helm, there’s a liminal quality to the level design with its blocky rooms, vaguely “computer lab” setpieces, and the occasional very rare sense that a room was supposed to represent something in particular. Each of the mappers, John Romero, Tom Hall and Sandy Petersen, bring their own distinct styles, though on the levels on which they collaborated it’s not always easy to tell who contributed what. Romero’s level design, which makes up the bulk of the first episode, is defined by relatively open spaces, and frequent contrasts in lighting, height variation and texture use. There’s a sense of mystery to exterior areas (especially once you realize that you can go outside in some spots) and Romero’s maps frequently loop in on themselves or require backtracking in a survival horror fashion. Given that this is the shareware episode, you’ll be facing low-level trash throughout, mostly hordes of zombies whose hitscan weaponry can make them dangerous in groups. Episode two is largely Tom Hall, and it shows, as he tends to fall back on his ideas for making realistic military bases and other installations, resulting in levels that are by and large quite flat. Despite this quality, it’s under Tom Hall that the aesthetic approaches anything resembling realistic, with crate mazes and secret labs, setting the earliest precedent possible for what would become “Russian realism” (see the likes of B0S Clan’s Sacrament mod and especially the various incarnations of Lainos’ Doxylamine Moon) and Doomcute, using level geometry to recreate real-world furniture and other items. Episode three is Sandy Petersen’s show: Hell is ugly, confusing, divorced from anything realistic, full of tricks and traps. Various techbase elements speak to the somewhat disordered development, but in-universe might be suggested to be parts of the Deimos lab subsumed by Satan’s dimension.

You should play Doom. Whether you’re a newcomer to the series looking to explore the old classics that made the shooter genre what it is, or a veteran of the 2016 reboot duology looking to explore the franchise’s history, Doom is a fantastic game. While the abstract level geometry might be off-putting to some — and I won’t lie, I get tired of it myself — the superb use of lighting and the overall liminal atmosphere, combined with straightforward, small-scale but high-intensity combat scenarios, provide a powerful action horror experience years before the likes of Resident Evil 4, Left 4 Dead, or the many Aliens-themed shooters that are on the market. (And let’s be real here: Doom is Aliens meets Evil Dead, is it not? It even began development as a licensed Aliens game before id Software chose to go their own direction. The arrival of the famous Aliens TC mod in November 1994 brought things full circle. Funny how things work out like that.)

Honestly, looking back on it now with thirty years of hindsight, I think what makes Doom work isn’t so much what it is as a mapset, groundbreaking as it is, but more what it is as a whole. While Doom II is by far the more popular choice for modding, there’s nothing quite like the original’s atmosphere; it’s this atmosphere that Doom 3 tried to build on, and I think at least in that regard it succeeded. Doom feels like a mix of everything id Software was into at the time, from violent sci-fi horror to Dungeons and Dragons, and they wear those influences on their sleeves. It’s heavy metal and horror, blood and violence and enough frenetic action to get the heart pumping. It is revolution, a flipping of tables, the great big bloody beast that terrified the shit out of busybody conservatives and bleeding-heart liberals and changed a generation of millennial kids who grew up on softer fare like Super Mario and Sonic the Hedgehog.

There’s a lot to look forward to in the Doom sphere. Obviously the reboot duology has been a smash hit, with a likely sequel on the way. The GZDoom engine, once a fork of Marisa Heit’s venerable ZDoom source port that greatly expanded what was possible for modders, has matured into a commercial-quality engine with games like Selaco and Supplice to look forward to — to say nothing of outright 2D sidescrollers like The Forestale and Operation Echo. Even Sergeant Mark IV, the man behind the controversial Brutal Doom, is getting in on the commercial game action. The community, always hardy and now almost unstoppable, continues to crank out banger mod after banger mod — when they’re not making commercial games like Supplice! If you like old shooters, or even if you like new shooters, the Doom community will almost certainly have something for you.

But sometimes it can be nice to just go back to where it all began.

Here’s to another thirty years. Rip and tear.

Episode One: Knee Deep in the Dead

Back in the day, many PC games were sold on the shareware model, in which an often generous portion of the game was distributed for free or relatively cheap. Many games, such as Doom, were thus divided into thematically distinct episodes, with the first episode intended as an extended teaser. “Knee Deep in the Dead” is almost entirely John Romero’s show, with a tightly managed design ethos that allowed for a consistent experience. Maps with contributions by the other two, or in the case of E1M8, done entirely without Romero, stick out like sore thumbs from Romero’s particular flow.

E1M1: Hanger

John Romero

The coveted E1M1 slot is the most important level in a game like Doom. It’s the level you use to sell the game, the first impression; if your first level isn’t fun, how can players be expected to keep playing? This isn’t anime. “Hangar” is short and sweet, a linear little teaser for what’s next, with a courtyard you can access if you know where to look.

E1M2: Nuclear Plant

John Romero

Romero’s freewheeling design ethos is most apparent here, a much larger offering divided into two wings. The east wing is where most of the shotgunners are, if you can find a way out into the yard. The west wing is much larger, though the bulk of it is an entirely optional maze of computer panels and strobing lights that hide a large hunting party of zombies and imps.

E1M3: Toxin Refinery

John Romero

On a superficial level it’s the same conceit as “Nuclear Plant,” with two separate wings to explore. But when you actually play it you’ll see the sheer genius of it with its varied setpieces and tantalizing secrets. Being able to open the secret path across the pit from the starting point is supremely satisfying.

E1M9: Military Base

John Romero

One of the odder offerings from Romero, “Military Base” is a set of about ten plain, boxy rooms in a grid pattern. The central cage full of imps will keep you busy while you mow down the zombie hordes, but the biggest threat is the horde of monsters teleporting in when you pick up the rocket launcher.

E1M4: Command Control

Tom Hall and John Romero

If you looked up “techbase” in the dictionary you’d see this map. The basic framework from Tom Hall is clear in the sprawling maze of corridors and big rooms, full of zombies and other beasties to kill. The central pagoda is the most interesting setpiece, but I’m partial to the elevator that only goes up once and the maze in the southwest. Infamously this map had a chamber with computers arranged in a swastika pattern in tribute to Wolfenstein 3D; later versions of the map wisely rearranged this to a less controversial symbol. Romero would eventually go back and do a more completely Romero take on the level with Phobos Mission Control.

E1M5: Phobos Lab

John Romero

This one feels curiously industrial compared to Romero’s other levels, with its sprawling pit of toxic goo and the catwalk you have to raise up to get to the yellow key. The horde of zombies and imps that come after you in the west room will be an unwelcome surprise, and even after all these years I still sometimes get caught out by it.

E1M6: Central Processing

John Romero

This and the following level are my favorites of the episode, the moment where Doom truly comes into its own with a sprawling, three-winged complex. What to highlight? Perhaps the massive ambush early on in the red key room? Or the maze of toxin storage chambers to the east? Perhaps the sheer wall of demons and spectres that are unleashed upon you in the penultimate encounter?

E1M7: Computer Station

John Romero

The pièce de résistance of the episode is an enormous dark maze of computers and vast chambers of toxic goo, divided into distinct sections. In true survival horror fashion, you’ll sometimes have to backtrack, only to bump into newly-unleashed monsters who were hiding in closets before heading off to look for you.

E1M8: Phobos Anomaly

Tom Hall and Sandy Petersen

The only level in the entire episode without any contribution from Romero, “Phobos Anomaly” is as straightforward as it gets, and utterly, irrevocably Sandy Petersen. The big finale has you fighting not just two Barons of Hell but also a horde of spectres in a dark, star-shaped chamber. Survive and the walls fall away, revealing a sinister teleporter. Step onto it and face the famous final ambush. And if you crave a more complete John Romero experience, he would reclaim the E1M8 slot for himself years later with Tech Gone Bad.

Final thoughts

“Knee Deep in the Dead,” as the shareware episode, is a great showcase of what Doom can offer. While the limited bestiary means you’ll be fighting mostly hordes of zombies, the freewheeling level design and strong theming makes for a memorable first outing.

Episode two: The Shores of Hell

For all that everyone praises John Romero’s level design, he disappears

entirely after “Knee Deep,” leaving Tom and Sandy to take over. Tom hardly

has a single level to himself; his design philosophy was largely at odds

with his fellows, and their fraying working relationship, in part driven by

Tom’s lack of enthusiasm for the project (Tom is a big kid at heart and

preferred the softer, more humorous vibe of

Commander Keen) eventually led to his ouster at id Software. Nevertheless, his influence

is clear in many levels given his predilection for big, semi-realistic

complexes.

E2M1: Deimos Anomaly

Tom Hall and Sandy Petersen

“Shores” gets things started with a bang. Far less sedate an opener than “Hangar” ever was, it strikes a different tone with dark grey brick walls, hordes of zombies and imps, and sinister architecture like the inverse cross right around the corner from the start point that damages you as you pass through it. This is also the first level we really get to see teleporters in, jumping around the various parts of a disconnected map. If you’re clever you’ll find an early plasma rifle, but be warned that it’s guarded on higher difficulties by what’s likely to be your first cacodemon.

E2M2: Containment Area

Tom Hall and Sandy Petersen

Years ago, the nerd culture site Old Man Murray had a running joke about the time it took from the start of a game to when you saw a crate or barrel since they were such common features. You can probably blame “Containment Area” for starting this trend with a sprawling crate maze full of imps, but storage wars are only part of the story. An optional armory has some goodies for you, but opening the supply closets means freeing the monsters within. It’s a pretty fun Tom Hall joint, with Hell’s corruption making itself felt in large parts of the map.

E2M3: Refinery

Tom Hall and Sandy Petersen

An odd level to say the least, this one feels like an intermission on your way to the next big thing. It’s positively crawling with cacos, but in spite of that it’s relatively flat and cramped without much room for them – or you – to maneuver. The big toxin chambers are pretty tricky with the narrow center walls making it tough to cross quickly. “Refinery” also marks the arrival of the Baron of Hell as an ordinary enemy; short of Cybie and the Spiderdemon, every enemy in the game is represented in this.

E2M4: Deimos Lab

Tom Hall and Sandy Petersen

Doom has always been pretty spooky but the back half of “Shores” is where the game is arguably at its scariest, with a moody soundtrack and lots of tough monsters. Much of the early part of the map winds around a toxic river, but as you work your way deeper into the lab you get to see some more sinister chambers like the red-light room in the north west, or the vine-choked circular room with the staircase leading to a teleporter.

E2M5: Command Center

Sandy Petersen

It’s not a Tom Hall level, but it sure feels like one, an enormous complex of winding paths and dead ends. The Baron and caco fight in the central room doesn’t give you a lot of room to maneuver; brave explorers will likely stumble upon the optional toxin vat in the northwest, but you’d have to make a trip down a long, poisonous hallway to get there. The secret level is really easy to find, it’s just a matter of knowing what switch does what.

E2M9: Fortress Of Mystery

Sandy Petersen

A pure gimmick map, consisting of two chambers, one with Barons and one with cacodemons. Savvy players will get these two groups to fight each other, and then pick off the survivors (usually the Barons.) Once they’re all dead you can grab all the stuff and get out of there. The caco corpses and tortured Barons ought to tell you how they feel each other.

E2M6: Halls Of The Damned

Sandy Petersen

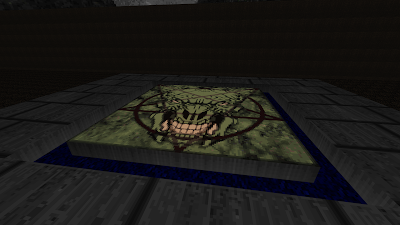

Probably my favorite level of the episode, “Halls of the Damned” is an ominous complex of setpieces, each with their own vibe. Sandy employs his tabletop roots to the fullest with all sorts of DnD fuckery, from the disappearing floor in the courtyard to the fake exit that drops you into a nightmarish chamber of blood and guts to be jumped by an ambush squad of monsters. The dark, wooden maze full of monsters is like E1M4’s imp-and-pinky warren on steroids.

E2M7: Spawning Vats

Tom Hall and Sandy Petersen

Tom Hall’s stamp of realism is most apparent in this level, with the sense that we’re really exploring some sort of twisted, corrupted laboratory. It starts you off on the run with some demons on your tail, but the rest of the map is a sprawling survival horror show. The shiny chrome lab area in the south central will tease you with the yellow key, but first you’ll have to deal with the horde of pinkies in the storage room. Great stuff – it’d be my favorite if not for “Halls of the Damned.”

E2M8: Tower Of Babel

Sandy Petersen

An even more straightforward boss level than “Phobos Anomaly,” “Tower of Babel” teases itself all throughout the episode as you can see it being built on the end-of-level screen. When you finally get to it, it can seem a bit underwhelming: a simple boss arena. And then you hear the roar of the Cyberdemon and the mechanical thumping of its hooves…

Final thoughts

People like to talk up “Knee Deep in the Dead” thanks to its tight design and their own fond memories of playing the shareware, but I think “The Shores of Hell” is a more complete picture of Doom in a nutshell. It’s darker, scarier, and meaner; its disordered design ethos and wild mishmash of textures that don’t always gel together speaks to the game’s somewhat haphazard development, but also enhance the unreality of a human installation being subverted by a dimension of pain and fear.

Episode three: Inferno

Welcome to the Sandy Petersen show. While Tom Hall does have his

contributions to this episode, the majority of the design is Sandy’s, and it

shows. It’s weird, ugly, full of traps, and leaves you with a sense of being

hunted. You’re in the devil’s domain now, kids. Saddle up.

E3M1: Hell Keep

Sandy Petersen

We kick things off with the memorable moment of rising up from a field of – is that supposed to be innards? tentacles? Whatever it is, it’s unsettling. Imps wander the field, but it’s the cacos just behind the front door that provide the real threat. Grabbing the shotgun and surviving the imp encounter beyond requires some fancy moves, but by that point you should have enough footing to deal with the rest of the level.

E3M2: Slough Of Despair

Sandy Petersen

Sandy’s penchant for idiosyncratic level design is at its most obvious here with a map in the shape of a grasping hand. There’s a sense of a hellish wilderness in this blasted moonscape, with each of the “fingers” forming a cave with their own mysteries to discover. If you can take down the zombies and other threats lurking the rocky canyon maze, you’ll be well on your way to arming yourself for the dangers ahead.

E3M3: Pandemonium Tom Hall and Sandy Petersen

What began as a control center in Doom’s early alpha days (back when it was much more similar to System Shock) is now a lost techbase, with much of it not even having been converted, but it still maintains both its Tom Hall-esque sprawling layout and its Sandy Petersen-esque unsettling aesthetics. The optional area to the east has some nice goodies, though be warned that it’s heavily guarded.

E3M4: House Of Pain

Sandy Petersen

No, not the rappers. A complex of torture chambers and other horrors, crammed to the brim with monsters. On an aesthetic level I like the chamber full of tormented souls chained to pillars, observable through a window in the far west; more relevant to the player are the “lungs” and “stomach” rooms by the starting point to the north, the latter having a pair of crushers guarding items you may want.

E3M5: Unholy Cathedral

Sandy Petersen

Ugh, I hate this level. While the appearance of flaming runes have implications about Hell’s language and culture, the actual map is a teleporter nightmare that’s difficult to navigate and full of high-level threats, especially the hot room to the northwest and the skull pit in the east from whence a horde of monsters arise, baying for your blood. Cool atmosphere if nothing else.

E3M6: Mt. Erebus

Sandy Petersen

Hell finally opens up again with a level that would anticipate the sprawling open complexes of Doom II, but be ready to be beset by swarms of cacos flying in over the burning lake and other threats wandering the island. Most any building you break into will trigger a siege from the hordes who want it back, but it’s the Y-shaped building in the northwest that induces the biggest response. Getting to the secret level requires a little planning, or at least some luck with straferunning.

E3M9: Warrens

Sandy Petersen

Wait, isn’t this just “Hell Keep?” It plays out exactly the same, though if you’re playing continuous you should be significantly better armed than you were the first go-round. Find your way through and step into the teleporter… only for the walls to fall away and reveal the truth about this level, with an angry cyberdemon staring you in the face. It’s a gimmick map, but it’s a good gimmick.

E3M7: Gate To Limbo

Tom Hall and Sandy Petersen

One last maze, awash in seas of toxic blood. For the size of the level, the relatively low monster count might seem like no big deal, until you realize just how much of the level is dangerous to stand in. More than anything though what stands out to me is the vibe, huge disconnected chambers with locked teleporter coffins, feeling a bit like some kind of hellish crypt complex.

E3M8: Dis

Sandy Petersen

Along came a spider… “Dis” is a boss arena that doesn’t give you much protection against the withering fire of the spiderdemon’s hitscan attack. If you’re feeling brave you can try to use the central pagoda as cover, but honestly if you have the BFG and you’re quick you can just dance on up to her and squash her before she’s had a chance to unload.

Final thoughts

Episode 3 is something of a mixed bag. Sandy’s vision of Hell doesn’t have a consistent theme; it’s a mishmash of ideas and aesthetics, leaning towards a traditional fire-and-brimstone look as opposed to the more gothic, even medieval aesthetics as seen in the likes of Quake, Hellraiser, and even later Doom games. I suppose the heavy metal soundtrack plays a part in that. Regardless, it’s still a fun ride with a lot of cool traps and weird shit to see.

-June <3

Do you know where you are, didn't anyone tell

You're a man on a

mission, you're on the shores of hell

Part of a series on Classic Doom

No comments:

Post a Comment